Biblia

- Bible -

Le "Codex Sassoon" exposé chez Sotheby's à New York est la Bible hébraïque la plus ancienne connue estimée à 30 à 50 millions de dollars

#Da ZH:

This blog is destined to keep general references sellected in the WEB. The address of the main blog is http://amicor.blogspot.com.

Le "Codex Sassoon" exposé chez Sotheby's à New York est la Bible hébraïque la plus ancienne connue estimée à 30 à 50 millions de dollars

#Da ZH:

How fingerprints get their one-of-a-kind swirls

No two alike: the patterns on a fingerprint arise from wave after wave of ridges that begin in various spots, spread towards each other and then collide.Credit: Tek Image/Science Photo Library

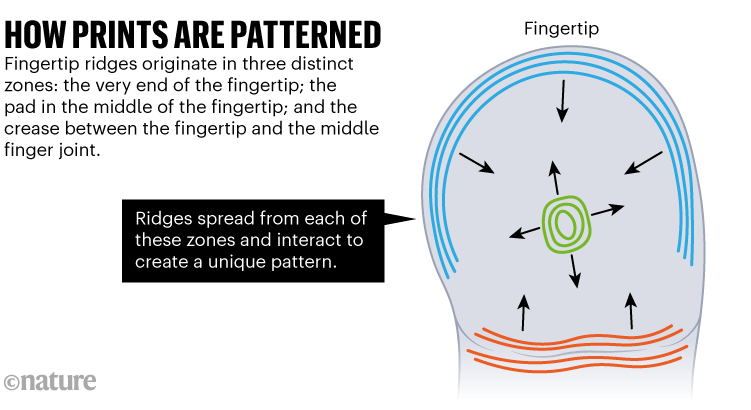

The whorls, arches and loops that make fingerprints unique are produced during fetal development by waves of tiny ridges that form on the fingertip, spread and then collide with each other — similar to the process that gives a zebra its stripes, or a cheetah its spots.

In a study1 published on 9 February in Cell, researchers found that the interplay between two proteins — one that stimulates ridge formation, and another that inhibits it — produces periodic waves of ridges that emerge from three distinct regions on the fingertip./.../

Durante uma época, andei envolvido com hereditariedade e impressões digitais e outras características que poderiam ter um determinismo genético. Andei inclusive colhendo amostras e tentando correlacionar com tendência familiar. Tinha lata com tinta preta, rolo para aplicação da tinta e coleta de padrões. Devo ter ainda e vou tentar fotografar. e colocar aqui as imagens.

To find the molecules that direct fingertip patterning, Headon and his collaborators studied the ridges on mouse toes, and human cells grown in 3D cultures. They found that a protein called WNT, which is important in hair-follicle development, stimulates ridge formation. Another molecule, called BMP, inhibits them, forming the Turing reaction–diffusion system.

Source: Ref 1.

The ridges emanate from three regions: the tip of the finger; the centre of the fingertip; and the crease at the base of the fingertip, where the finger bends (see ‘How prints are patterned’). In simulations, Headon and his team altered the timing, angle and precise location of the waves’ origins in these three sites, and created arches, loops and whorls. “These waves will collide,” says Cheng-Ming Chuong, a developmental biologist at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. “And when they collide, they provide a turbulence that helps to create the diversity of fingerprint patterns.”

Dr. James Jude, a thoracic surgeon whose recognition that external manual pressure could revive a stalled heart, and who used that insight to help develop the lifesaving technique now known as cardiopulmonary resuscitation, or CPR, died on Tuesday at his home in Coral Gables, Fla. He was 87.

The cause was complications of a Parkinson’s-like neurological disorder stemming from a tick bite, his son Peter said.

In the late 1950s, Dr. Jude was a resident at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, experimenting with induced hypothermia as a way to stop blood flow to the heart by cooling it down and allowing surgical procedures to be performed without fatal loss of blood.

In experiments with rats, he found that hypothermia often caused cardiac arrest, a problem that two electrical engineers down the hall were addressing in experimental work on dogs, using a defibrillator to send electrical shocks to the heart. William Kouwenhoven, the inventor of a portable defibrillator, and G. Guy Knickerbocker, a doctoral student, had seen that the mere weight of the defibrillator paddles stimulated cardiac activity when pressed against a dog’s chest.

Dr. Jude immediately saw the potential for human medicine and began working with the two men.

In July 1959, when a 35-year-old woman being anesthetized for a gall bladder operation went into cardiac arrest, Dr. Jude, instead of using the standard technique of opening the chest and massaging the heart directly, applied rhythmic, manual pressure.

“Her blood pressure came back at once,” he recalled. “We didn’t have to open up her chest. They went ahead and did the operation on her, and she recovered completely.”

In 1960, the three partners published an article in The Journal of the American Medical Association, “Closed-Chest Cardiac Massage,” reporting that when the technique was used on 20 patients, ranging in age from 20 months to 80 years, 14 of them resumed normal heart function.

“Anyone, anywhere, can now initiate cardiac resuscitative procedures,” the authors concluded. “All that is needed is two hands.”

Cardiac massage evolved into CPR when Dr. Jude and his team collaborated with doctors at Baltimore City Hospitals (now Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center) who had been working on pulmonary resuscitation, a noninvasive method of restoring lung function. Neither team had known what the other was up to, but when the two were brought together, their techniques were combined to create what they called “heart-lung resuscitation.”

The American Heart Association, which formally accepted the technique in 1963, renamed it cardiopulmonary resuscitation, believing that term to sound more professional.

Dr. Jude became a missionary for CPR, appearing before medical groups around the country to explain the benefits of the technique, which was gradually adopted by fire departments, police departments, paramedical services and hospitals around the world.

James Roderick Jude was born on June 7, 1928, in Maple Lake, Minn. After attending St. Thomas College (now the University of St. Thomas) in St. Paul as a pre-med student, he enrolled at the University of Minnesota, where he completed his bachelor’s degree and graduated in 1953 from its medical school. He chose Johns Hopkins for his surgical internship and residency because it was in Baltimore, the hometown of his wife, the former Sallye Garrigan.

Mrs. Jude, a prominent environmentalist and preservationist in South Florida, survives him, as do their sons Roderick, John, Robert and Christopher; their daughters Cecilia Prahl and Victoria Steele; his sister, Monica Loch; 13 grandchildren; and three great-grandchildren.

After helping develop CPR and serving as an attending surgeon and professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins, Dr. Jude was a professor of surgery and chief of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery at the University of Miami School of Medicine and Jackson Memorial Hospital in Miami. There, he and several colleagues outfitted some of the first mobile cardiac units and trained paramedics in CPR. In 1971, he went into private practice, from which he retired in 2000.

He was the author of “Closed Chest Cardiac Resuscitation: Methods, Indications, Limitations,” published by the American Heart Association in 1966, and the co-author, with James O. Elam, of “Fundamentals of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation” (1967). He was also a co-author of “Coping with Heart Surgery and Bypassing Depression” (1991).

Dr. Jude played down his importance in developing CPR, a breakthrough that The Journal of the American Medical Association had recently compared to the discovery of penicillin.

“It was just serendipity — being in the right place at the right time and working on something for which there was an obvious need,” he told the alumni newsletter of the University of St. Thomas in 1984. “Things like that happen in medicine all the time.”